Back to the Basics

Hello hello! This is Aleks speaking! If you do not know me: I am the co-founder of apn gallery and I am working on the business side of the company whereas my co-founder and dear friend Marika works on the visual side of things, since she is also a great fashion designer.

Welcome to the first sustainability blog. Today’s blog is all about the basics. I thought that it was a good idea to talk about the status quo of the fashion industry to make sure that we are on the same page. To give you a short overview of today’s topics I will start with a very broad approach defining the term “sustainability” in my own words and focusing on the world’s “health condition”. Furthermore, I will mention some general facts and some insights about the environmental pollution of the fashion industry. This is going to be followed up by talking about overconsumption. The blog will end with some thoughts on ideas about the future of the fashion industry. With that being said let us jump into it.

What does it mean to be “sustainable”?

The problem with the word “sustainable” or “sustainability” is that it is not legally protected or clearly defined. Therefore, everyone can state that they are ecologically or socially sustainable. However, the most precise definition (in my opinion) of sustainability comes from Brundtland & Khalid (1987) who define sustainability as follows: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Regarding the negative environmental changes that are happening in the world, I would go one step further and say: “Sustainability means meeting the needs of the present in a way that improves social and ecological issues to ensure that future generations can live without any compromises.” In short, this means: Solving today’s ecological and social challenges so that future generations can live on this planet like we did.

What are the “Planetary Boundaries”?

Let us take a closer look at the “health condition” the planet is in. Currently, we are living in a geological epoch called the “Holocene”, which already existed for 11,700 years and is the only known state of the earth in which we as humans can live. However, due to the continuous destruction by humans of the planet, we are about to move into a whole new geological epoch called the “Anthropocene”. Without going too much into detail, it is very likely that this new epoch is much more hostile when it comes to living conditions for humans than the current state. Therefore, scientists have developed a model called “planetary boundaries”. At its core, the planetary boundaries define a safe operating space in which we humans can live and interact without risking shifting into a different geological epoch.

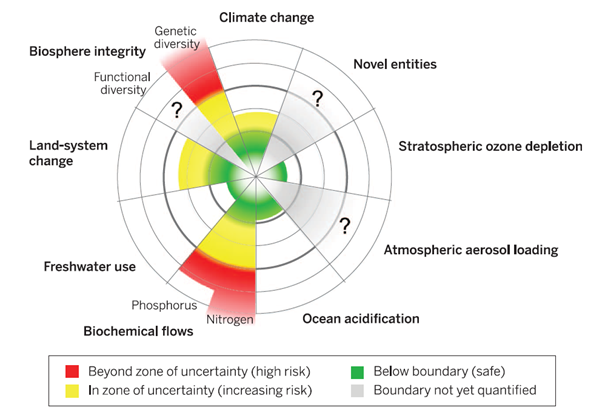

In total, there are nine boundaries. The most important ones are “climate change” and “biodiversity” because crossing the boundary of only one of these two alone would be powerful enough to irreversibly harm the earth's system and thereby transform the state of the earth we currently live in. To have an early warning approach the boundaries were set lower than the biophysical threshold to include insecurity and buffers (Steffen, W., et al. 2015). As you can see in the graphic below climate change is increasingly developing beyond the zone of uncertainty, but it is not too late yet. Secondly, the genetic diversity in the biosphere integrity dimension is drastically threatened.

Figure 1: “Planetary Boundaries”, Steffen, W., et al. 2015

So, you might ask yourself: Why am I reading something about planetary boundaries if I wanted to read something about the fashion industry? Because the fashion industry has a significant effect on exactly the two mentioned critical boundaries. The reason for that is that the concept of fashion itself is very linear. This means that materials get extracted, clothes are made, then worn, and then discarded. This means that nearly nothing of the finished garments are reused again because the clothing itself was never designed like that. Additionally, overconsumption is driving the raw material extraction which ultimately leads to us buying clothes that we do not need. Basically, we do not need to buy clothes on a regular basis in the way we are doing it now.

Little sidestep: In 2020 around Christmas I decided that I would not buy clothes in 2021. During this year of fasting, I allowed myself to only wear clothes that were already in my possession. In the beginning, I was afraid that I did not have enough clothes to make it through the year. However, I soon recognized that there was nothing to worry about. I even sold some clothes that I never wore. Surprisingly, I witnessed that I could go on with this challenge for quite a few years.

This brings me to the following conclusion: From a rational perspective we do not need to buy new clothes to “survive”. I am pretty sure that your closet is well-equipped, too. However, from the perspective of the fashion victim that lives inside me I would conclude that we as humans will never stop buying new clothes because we are no idealistic machines. Therefore, we should at least produce and buy clothes as ecologically and socially sustainable as possible while simultaneously focusing on our overall consumption of clothes. Additionally, to get an understanding of how strongly the fashion industry influences the planet we must realize how significant the negative impacts are going to be if we do not act now. Of course, every industry has to drastically improve its sustainability performance, but the fashion industry is a big player when it comes to environmental pollution. With that being said, we can move on to the next chapter.

The difference between fast fashion and slow fashion

First things first: We have to differentiate between two business strategies: Fast fashion and slow fashion. The term “fast fashion” can be defined as a business strategy to offer the latest fashion trends for low prices as fast as possible in your store. (Bick, R., Halsey, E., & Ekenga, C. C. 2018) Additionally, most of the clothes are manufactured in far eastern countries like India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar in order to save labor costs. Two of the most famous examples of fast fashion are Zara and H&M. Even though Zara focuses on a higher degree of fashionability, both labels can be seen as the pioneers of fast fashion. Little sidestep: Back in the days, before these two companies went through the roof with this business strategy, clothes were much more expensive. As a result, the number of clothes humans possessed (especially in the western countries) was significantly smaller. However, the principle of fast fashion is often referred to as the “democratization” of clothes because now many people are able to wear the latest trends even though the person’s financial income is low.

Let’s talk about the pendant of fast fashion: Slow fashion. As the name already suggests this strategy is the complete opposite of fast fashion. This emerging form of fashion retail focuses “on production principles that encourage increased lifecycles of products, reduced volume of purchasing by individuals, and ethical care in production and sales.” (McNeill, L. S., & Snowdon, J. 2019) I think it is quite obvious that slow fashion has a rather small negative impact on the fashion industry as it only made up for 2 % of the whole fashion market in 2020 (Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020). Therefore, in the following blogs, I will mainly focus on fast fashion retailers and the industry behind them because this part of the industry has the largest environmental and social impact. Of course, I will also write about the negative impacts of the luxury fashion industry. However, now that we defined “fast fashion” and “slow fashion” we can move on to the next section and speak about hard facts.

General facts about the fashion industry

The fashion industry has a global value of 3 trillion dollars (3,000,000,000,000$).This accounts for 2% of the global gross domestic product.[1] With 3 trillion dollars you could buy Buckingham Palace. 3000 times. The largest corporations/conglomerates (a conglomerate is a corporation that consists of many other corporations) are LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy), Nike, and Inditex (this conglomerate also contains Zara and Pull & Bear). Over 80 billion pieces of clothing are produced every year (Bick, Halsey, & Ekenga, 2018). Additionally, around 66 tons of textile clothing end up in landfills per year while the production of textiles is still increasing (Shirvanimoghaddam et al. 2020). “Similarly, global consumption has risen to an estimated 62 million tonnes of textile products per year, and is projected to reach 102 million tonnes by 2030”(Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T., & Gwilt, A. 2020). Unfortunately, only 1% of the total textile waste is recycled into new garments[2]. The reasons for that are so complex that I could write a blog entry only about that. In short, the main issue is that many clothes consist of different materials (e.g., cotton and polyester blends), which makes it more difficult to recycle garments into new yarns in the first place. More about that in a future blog entry!

Moving on, over 10% of the total CO² emissions are caused by the fashion industry.[3] Additionally, the fashion industry accounts for over 20% of the total water pollution[4]. Per year this industry consumes around 79 trillion liters of water (Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T., & Gwilt, A. 2020). This is the amount of water that is in the world’s largest lake. (Kosarev, Aleksey et al. 2021) The Caspian Sea. So, each year the fast fashion industry drains the world’s largest lake. I understand that these numbers sound intimidating. However, I always say that if you want to change something you must go where it hurts. Nevertheless, I will assure you that I will end today’s blog with some promising ideas that this blog ends on a good note!

Overconsumption

As you might have guessed it: Fast fashion is not the yellow from the egg to put it gently. This business strategy nurtured us as consumers to constantly buy more clothes than we need and at the same time throw them away even faster. Compared to the year 2000 we bought 60% more clothes in 2014 and threw them away twice as fast.[5] To make things worse: There is a large discrepancy between the number of clothes consumers think they wear versus the number of clothes they actually wear. According to Hohmann (2018), the population of the USA is convinced that they wear 57% of the items inside their wardrobes. The actual number is 18%. This tells us two things:

Firstly, we need fewer clothes than we purchase.

Secondly, most consumers are aware that they are wearing less than half of the clothes they already own. However, they continue to buy new clothes. This results in actively financing mass production.

Another problem that arose as a consequence of overconsumption is the continuously rising pressure on manufacturers to produce more clothes in less time due to an ever-increasing demand. As a result, this led to unethical working conditions. The most famous example is the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh in April 2013. Approximately 1,130 workers died and over 2,000 were injured (Mamun & Griffiths, 2019). Until today, this incident is treated as a flagship for the negative impacts of fast fashion. Many factors were mentioned (e.g., poor construction standards, and poor working conditions (Mamun & Griffiths, 2019)) but the main reason for this incident was the pressure of fast fashion companies leading to poor safety conditions in the factory (Aggarwal & More, 2020). Retailers like H&M, Zara, and Primark are constantly demanding faster production cycles and lower production prices. This results in the exploitation of workers along the supply chain reflected by low wages, poor working conditions, and long working hours (Aggarwal & More, 2020).

In case you feel a little intimidated: You are not the only one who feels this way. However, there are still enough people out there who do not know anything about what is going on in this industry. Even in this blog we barely touched the surface. Therefore, it is you and me who have the responsibility to go out there and spread the message to raise awareness for this topic.

And now; as promised, I will end today’s blog with some positive thoughts.

Somebody once told me that a disadvantage always comes with an advantage. What do I mean by that? Even though the fashion industry (especially the fast fashion part of it) is one of the dirtiest industries that mankind has ever seen – it offers various sustainable business innovation opportunities triggered by significant market failures regarding ecological and ethical sustainability. I will elaborate on these kinds of ideas in one of the following blogs but let me give you a brief insight into my head: Fashion brands (even most of the “sustainable” ones) fail to truly incorporate ecological and social sustainability inside their business core. Of course, many companies have a division for corporate social responsibility (CSR) but at the end of the day, this division is trying to compensate for regularly being a polluting and exploiting company. Spending tremendous amounts of money alone will not do the trick if you continue doing business as usual. As a little “homework” try to think about the following Idea: What if we changed the core business of a fashion brand? From being only profit-oriented to being people, planet, and profit-oriented?

“The world as we have created it is a process of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking.” -Albert Einstein

Lots of Love,

Marika & Aleks

Bibliography

Aggarwal, N., & More, C. (2020). Fast Fashion: A Testimony on Violation of Environmental and Human Rights. International Journal, 1(3).

Bick, R., Halsey, E., & Ekenga, C. C. (2018). The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environmental Health, 17(1), 1-4.

Brundtland, G. H., & Khalid, M. (1987). Our common future: Oxford University Press, Oxford, GB.

Hohmann, M. (2018). Umfrage zum Anteil der ungetragenen Kleidung nach Ländern weltweit in 2018 Retrieved from: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/895676/umfrage/umfrage-zum-anteil-der-ungetragenen-kleidung-nach-laendern-weltweit/

Kosarev, Aleksey Nilovich , Leontiev, Oleg Konstantinovich and Owen, Lewis. "Caspian Sea". Encyclopedia Britannica, Invalid Date, https://www.britannica.com/place/Caspian-Sea. Accessed 27 November 2021.

Mamun, M. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). PTSD-related suicide six years after the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh. Psychiatry research.

McNeill, L. S., & Snowdon, J. (2019). Slow fashion–Balancing the conscious retail model within the fashion marketplace. Australasian marketing journal, 27(4), 215-223.

Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T., & Gwilt, A. (2020). The environmental price of fast fashion. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1(4), 189- 200. Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T., & Gwilt, A. (2020). The environmental price of fast fashion. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1(4), 189-200.

Shirvanimoghaddam, K., Motamed, B., Ramakrishna, S., & Naebe, M. (2020). Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Science of The Total Environment, 718, 137317.

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., De Wit, C. A. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347.

[1] https://fashionunited.com/global-fashion-industry-statistics/

[2] https://theroundup.org/textile-waste-statistics/

[3] https://unfccc.int/news/un-helps-fashion-industry-shift-to-low-carbon

[4] https://unfccc.int/news/un-helps-fashion-industry-shift-to-low-carbon

[5] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula